the tree of life

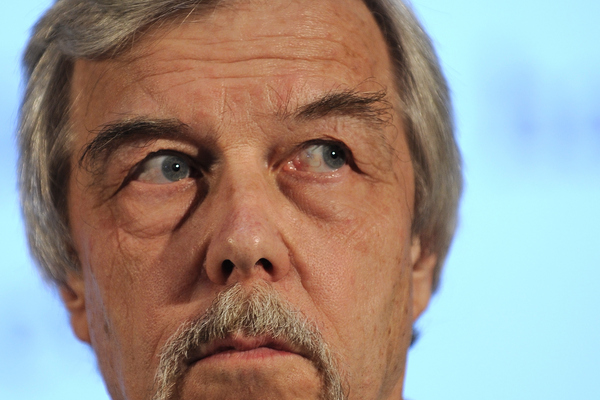

Brad Pitt on Terence Malick & The Tree of Life:

Terry has an embrace for Christianity, for all religions, but not in the textbook definition of Christianity. You're looking at a man who loves science, and has an interpretation and a feeling for God. In America those two things usually don't coincide. And yet he sees the two as one: he sees God in science and science in God.I also grew up in a Christian environment, and as I became an adult — it doesn't work for me. I hesitate to say anything about religion, and yet I think I should say it, when so many wars are spawned by it. I got my issues; I can't talk about it without getting a little bit hot. It's probably not best for me to talk about that. But I was actually very comfortable playing within the religious iconography, because I lived that.

I'd say that Tree of Life is not a Christian so much as a spiritual film. I was surprised, watching it last night, how powerfully it struck me. What the film was saying to me is that there is an unexplained power; there is this force. And maybe peace can be found, but not by trying to explain it with the religion. Maybe there's peace to be found just in that acceptance of the unknown.

via TIME.

faith & science

The European: Do you think it is conceivable that we will eventually learn something about before the Big Bang?

Heuer: I doubt it.

The European: How do you make sense of that paradox? You want to expand the realm of knowledge but at some point, there is a definite boundary that you cannot cross. Do you simply have to accept the fact that nothing was prior to the Big Bang?

Heuer: I wasn’t saying there was nothing, I am saying that we don’t know anything about what was before – if there was a before. But here we are crossing the boundary between knowledge and belief. I think many famous scientists have struggled with this question and people today also struggle with it.

The European: So at the very borders of human knowledge, science and belief tend to converge?

Heuer: In the scientific community we don’t tend to discuss such things too often. But the more we investigate the early universe, the more people are trying to connect science to philosophy. That is a good thing. Since we are struggling with the limits of knowledge, maybe philosophy or theology struggle also with our research. I think it is important that we open a constructive dialogue. We are currently planning seminars and workshops to do exactly that. My hope is that we can reach a common understanding of what we are talking about.

time

Although Eagleman and his students study timing in the brain, their own sense of time tends to be somewhat unreliable. Eagleman wears a Russian wristwatch to work every morning, though it’s been broken for months. “The other day, I was in the lab,” he told me, “and I said to Daisy, who sits in the corner, ‘Hey, what time is it?’ And she said, ‘I don’t know. My watch is broken.’ It turns out that we’re all wearing broken watches.” Scientists are often drawn to things that bedevil them, he said. “I know one lab that studies nicotine receptors and all the scientists are smokers, and another lab that studies impulse control and they’re all overweight.”

via The New Yorker.